I created a video quiz about 20 figurative expressions we often use in French. In this article, I’ll give additional information about those expressions and how to use them exactly. If you want to test your knowledge, play the quiz before you read the explanations.

As usual, a French-only version of this article is available. I highly encourage you to read it if you want to improve your reading skills in French, and use this English version if you need support.

Video quiz: Figurative expressions in French

- Video quiz: Figurative expressions in French

- Explanations of 20 French figurative expressions

- Se dépenser

- Se prendre la tête

- Être à l’ouest

- Ne pas être dans son assiette

- Donner un coup de main

- Tourner la page

- Mettre les pieds dans le plat

- Avoir un poids sur les épaules

- J’en peux plus !

- Reprendre du poil de la bête

- Mordu / Mordue de

- Voler de ses propres ailes

- Reste pas planté / plantée là !

- Ne pas y aller par quatre chemins

- Soûler

- Jeter un blanc froid

- Pousser à (+ verb)

- Pousser à bout

- Avoir beau

Explanations of 20 French figurative expressions

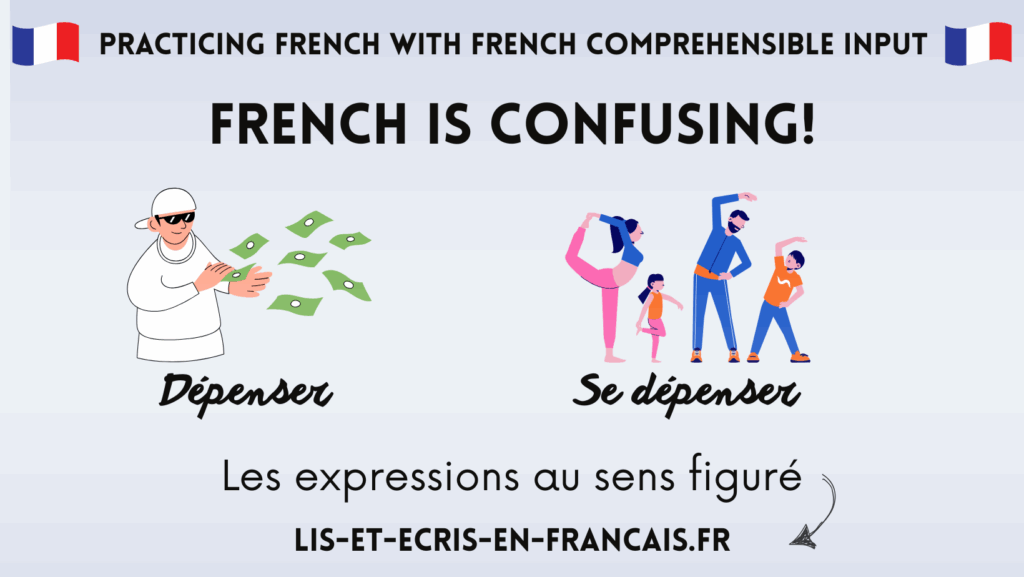

Se dépenser

Usually, “dépenser” relates to money. It can be translated by “to spend”.

We also use that verb when talking about calories. In that case, “dépenser” means burning.

- Après une heure de vélo à la salle, je n’ai dépensé que 300 calories. (After one hour biking at the gym, I’ve only burnt 300 calories.)

It’s also used when talking about one’s energy.

- J’ai dépensé toute mon énergie à repeindre la salle de bain. Maintenant, je vais faire une sieste ! (I spent all my energy painting the bathroom. Now, I’m gonna nap!)

In the quiz, I’ve used the pronominal form “se dépenser”. It usually means doing sports, or any activity that makes you move and spend some energy.

- Je me suis bien dépensée à la salle de sport, j’étais trempée de sueur ! (I worked out hard at the gym, I was drenched in sweat!)

- Les enfants ont besoin de se dépenser, ce n’est pas bon de les forcer à rester assis pendant des heures. (Kids need to move, it’s not good forcing them to sit for hours.)

- Quand il est stressé, il aime courir pour se dépenser. (When he’s under pressure, he likes to run to burn off energy.)

Se prendre la tête

When we hear this expression, we figure someone taking their head into their hands.

We can “prendre la tête à quelqu’un” (literally, “take someone else’s head”), which means make them angry or annoyed. One can also say that “quelque chose / quelqu’un me prend la tête” (literally, “something / someone is taking my head”).

- Ma mère me prend la tête à toujours me demander de ranger ma chambre ! (My mother is always giving me a hard time, asking me to tidy my room!)

- Ce jeu vidéo me prend la tête, je n’arrête pas de perdre au même niveau. (That video game frustrates me, I keep on losing at the same level.)

“Se prendre la tête” (pronominal) means getting angry or annoyed, or making one’s own life complicated.

- Je devrais arrêter de me prendre la tête avec le travail, ça m’obsède même le weekend. (I should stop worrying about work, it obsesses me even on weekends.)

- Je ne sais pas pourquoi tu te prends la tête avec cette tâche, de toute façon il faut recommencer toutes les semaines. (I don’t know why you’re bothering with this task, you have to start again every week anyway.)

- Tu n’aurais pas dû te prendre la tête avec ton patron, tu risques des répercussions. (You shouldn’t have gotten into a fight with your boss, there might be consequences.)

When talking about something (“se prendre la tête à propos de quelque chose”), there’s often an implied sense of uselessness. Meaning, not only are we getting angry, annoyed or frustrated about something, but above all, it’s no use getting emotional about it. We often use the colloquial expression “Tu te prends trop la tête” (literally “You’re taking your own head too much”), which means “you should take it easier, less seriously, there’s no use getting emotional about this, make your life easier”.

Être à l’ouest

“L’ouest” (the West) is one of the four cardinal directions (in French: est, ouest, nord, sud), the ones you can see on a map or compass. In French, intermediate directions are called: nord-est, nord-ouest, sud-est, sud-ouest.

“Être à l’ouest” (literally, “To be in the West”) means being absentminded or inattentive, to the point you kind of forgot what you were doing or lost your marks.

- Tu n’arrêtes pas de gaffer depuis quelques jours, tu as l’air complètement à l’ouest ! (You’ve been very clumsy for the past few days, you seem completely out of it!)

- Il était totalement à l’ouest pendant la réunion : il n’entendait pas quand on lui posait une question, il a renversé un verre d’eau sur son ordinateur, il avait l’air perdu par rapport au sujet alors qu’il a travaillé dessus pendant des mois… (He was completely lost during the meeting: he didn’t pay attention when someone asked him a question, he spilled a glass of water on his computer, he seemed lost on the subject even though he had been working on it for months…)

When one’s really lost, we say they’re “complètement à l’ouest” (literally, “completely to the West”).

There are other expressions to talk about being absentminded, like “être dans la lune” (literally, “to be in the moon”) or “être tête en l’air” (literally, “to be head-in-the-air”). In those two expressions, we can figure someone looking up (to the moon or in the air), which is something we often do unconsciously when we’re lost in thoughts or daydreaming. Yet another expression used in French is “avoir la tête ailleurs” (literally, “to have one’s head elsewhere”).

Other expressions using directions include “perdre le nord” (literally, “to lose the North”), which means being lost (both figuratively and literally). Maybe that’s why we say “être à l’ouest” (“to be in the West”)? If you are in the West, it means you might have lost the North!

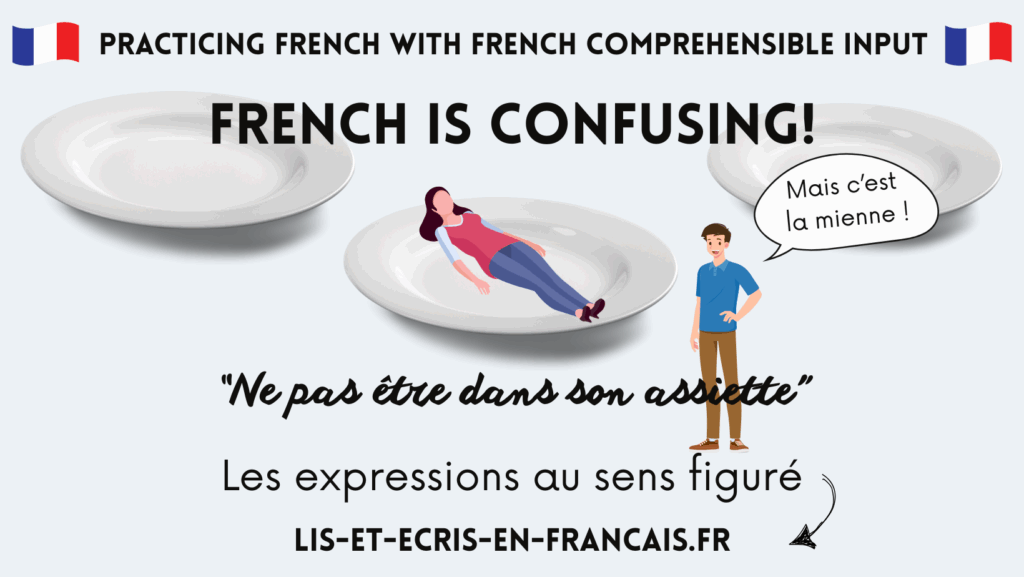

Ne pas être dans son assiette

This French expression is only used in the negative form, we don’t say “être dans son assiette”.

Although the expression literally translates to “not being in one’s plate”, it bears no link with food. It just means “not feeling well, not feeling at ease, feeling sick or tired“. We often say “Il / Elle n’a pas l’air dans son assiette”, which means we notice someone doesn’t look well.

Donner un coup de main

This one’s easier because it can almost literally be translated to “To give a hand” in English (and there’s an equivalent expression in many languages). French is slightly different because we give “un coup de main” (literally, “a hit of hand”), although there’s no violence involved! “Un coup” gives an impression of something small, temporary, short. The expression doesn’t necessarily involve helping in a manual way, although the word “hand” appears in the expression.

- J’ai donné un coup de main à ma sœur pour étudier son cours de biologie. (I helped my sister study for her biology class.)

- Elle s’est arrêtée et a donné un coup de main à l’automobiliste arrêté qui n’arrivait pas à changer son pneu. (She stopped and gave a hand to the driver who was stopped and was unable to change his tire.)

There’s a very similar expression in French that has a different meaning: “avoir le coup de main” (literally, “to have the hit of hand”), which means to be good at something manual. In English, it can translate to “to have a knack”.

- Cet apprenti a le coup de main, il travaille la pâte avec agilité et ses pains sont toujours bien réussis. (This apprentice has a knack for making bread, he works the dough with agility and his breads always turn out well.)

- Pour faire démarrer cette vieille voiture, il faut avoir le coup de main ! (To get this old car started, you need to have a knack!)

- Au début, il avait du mal à peindre, mais après quelques minutes il a attrapé le coup de main. (At first he had trouble painting, but after a few minutes he got the hang of it.)

Tourner la page

The figurative expression “tourner la page” (literally, “to turn the page”) is quite easy to figure out: when you turn a page, you move on. Another French expression related to books with a similar meaning is “clôturer un / le chapitre” (literally, “to close a / the chapter”). “Tourner la page” is often used in situations where you have to forget something or accept something, a moment of life that is not easy or nice, in order to be able to move on. For example, after loosing your job, breaking up, getting sick…

- Tant qu’elle n’aura pas tourné la page de son divorce, elle n’arrivera pas à rencontrer quelqu’un d’autre. (Until she gets over her divorce, she won’t be able to meet someone else.)

- Oh c’est bon, il est temps que tu tournes la page ! J’en ai marre que tu me répètes tout le temps cette histoire. (Come on! It’s high time you move on! I’m sick of you telling me this story over and over again.)

Mettre les pieds dans le plat

“Mettre les pieds dans le plat” (literally, “put one’s feet in the dish”) means raising an embarrassing topic, something people are trying to avoid, in a very direct way. It can more or less be translated by “to put one’s foot in it” in English.

- On voyait bien qu’ils s’étaient disputés et on évitait tous le sujet, mais Manon a mis les pieds dans le plat et leur a demandé pourquoi ils faisaient la gueule ! (We could see they had an argument and we were all avoiding the subject, but Manon put her foot in it and asked them why they were sulking!)

Originally, this expression suggested that the person who put their foot in made it without realizing in, without the intention to embarrass others. Nowadays, the French expression “mettre les pieds dans le plat” can also be used when someone did it intentionally, with the objective of embarrassing others.

- Je savais qu’elle n’avait pas fait son boulot et que de sa faute, on allait perdre le contrat avec ce client. Du coup, j’ai mis les pieds dans le plat pendant la réunion pour que notre manager soit au courant ! (I knew she hadn’t done her job and that because of her, we were going to lose the contract with this client. So, I put my foot in it during the meeting so our manager would know!)

Avoir un poids sur les épaules

“Avoir un poids sur les épaules” (literally, “to have a weight on the shoulders”) means we have so many responsibilities that we feel like they physically crush us.

And when it gets better, we feel like we’re “libéré d’un poids” (literally, “freed from a weight”).

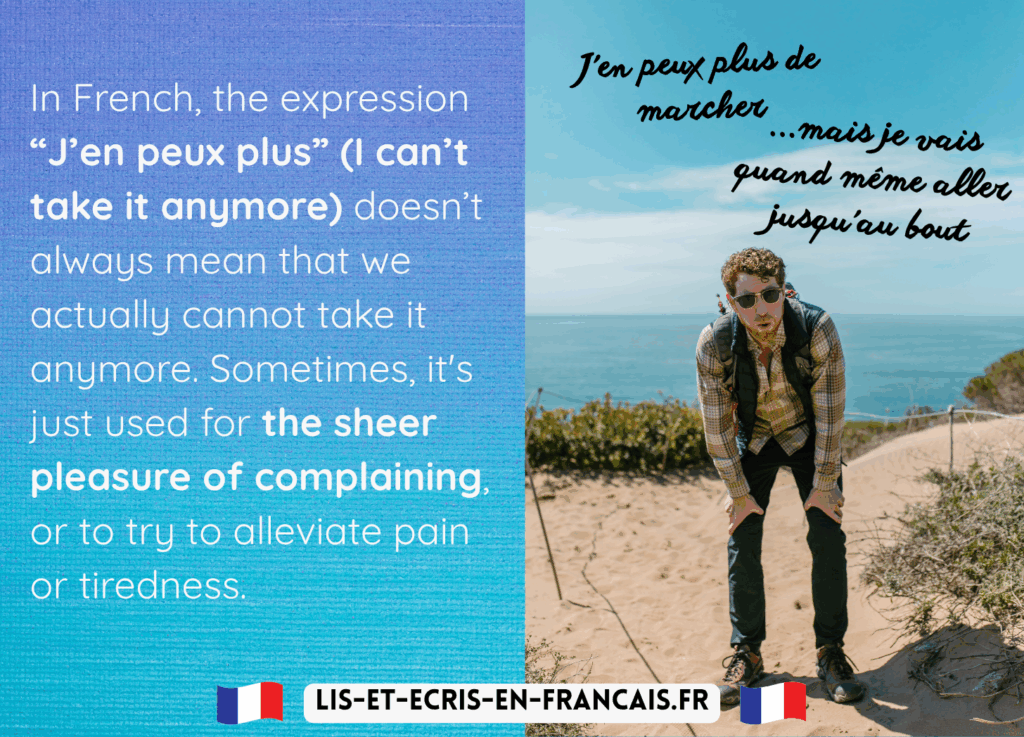

J’en peux plus !

We often use this colloquial expression, although it’s not grammatically correct. “J’en peux plus” is a shorthand of “Je n’en peux plus”, but you probably already know that, in French, we regularly skip the “ne / n'” that is part of the negation, to only keep “plus” or “pas”. Again, it’s not grammatically correct and is to be avoided in official written communications, but in day-to-day oral and written communication, it’s really common.

- Correct: “Je ne veux pas travailler !” => Actually used: “Je veux pas travailler !”

- Correct: “Je ne veux plus jamais te voir !” => Actually used: “Je veux plus jamais te voir !”

- Correct: “Désolée, je n’ai pas de monnaie.” => Actually used: “Désolée, j’ai pas de monnaie.”

“J’en peux plus”, or “Je n’en peux plus” (literally “I cannot of it anymore”), means one cannot bear someone anymore, one is exhausted of something. It can be very negative (complaint, exhaustion) or more neutral (factual, descriptive).

- Je n’en peux plus, j’ai trop mangé, je ne pourrais plus rien avaler ! (I can’t anymore, I ate too much, I cannot swallow anything more! => this is factual, describing a physical state)

- Je n’en peux plus de tes caprices, je te quitte ! (I cant take your whims anymore, I’m leaving you!)

- J’ai marché toute la journée, je n’en peux plus, mes jambes me font mal. (I’ve been walking all day, I can’t take it anymore, my legs hurt.)

- J’ai essayé de tenir bon au travail mais je n’en peux plus des règles absurdes et des collègues qui ne font pas leur boulot : je me casse ! (I tried to hold on at work but I’m so done with all those farfetched rules and those colleagues who are not up to their job: I’m leaving!)

In each case, this expresses a limit that was reached. However, when using this expression, we don’t always mean that we actually can’t take it anymore. Sometimes, it’s just used for the sheer pleasure of complaining, or to try to alleviate pain or tiredness.

For example, if you’re on a hike, you can complain “je n’en peux plus de marcher, j’ai mal aux jambes” (I can’t walk anymore / I can’t take it anymore, my legs hurt), but you’ll continue walking because you have to make it to the end anyway. It’s just a way to complain because you’re pushing your limits, even if you know you have to keep pushing.

Another useful information: “J’en peux plus” is sometimes shortened to “JPP” in written conversations (especially by young people).

Reprendre du poil de la bête

This expression (literally, “To take back some hair from the beast”) means regaining energy and motivation after a period of demotivation and/or tiredness.

- Elle est restée malade pendant trois semaines à cause du Covid, mais maintenant elle a repris du poil de la bête : elle est encore plus énergique qu’avant ! (She was sick for three weeks because of Covid, but now she’s back on track : she’s got more energy than before!)

- J’étais déprimée au travail, mais depuis que le nouveau patron est arrivé j’ai repris du poil de la bête. (I was depressed at work, but since the new boss arrived, I found my motivation back.)

Mordu / Mordue de

The expression “être mordu / mordue (de quelque chose ou de quelqu’un)” (literally, “to be bitten by something or someone”) means being crazy in love with someone or super passionate about something.

- Je suis mordue d’écriture, j’ai déjà publié 3 romans. (I have a passion for writing, I already published 3 novels.)

- Il est mordu d’elle, mais elle en pince pour quelqu’un d’autre. (He’s mad about her, but she likes someone else.)

- Il ne rate jamais un match de foot, il est complètement mordu. (He never misses a football match, he’s completely mad about football.)

“Mordu / Mordue” (“bitten”) is also used as a noun to talk about someone who’s very passionate about a topic.

- C’est un mordu de cinéma, il connaît tous les classiques. Sa femme est une mordue de musique. (He has a passion for cinema / He’s mad about cinema, he knows all the classics. His wife is passionate about music.)

Voler de ses propres ailes

This expression (literally “to fly with one’s own wings”) means being autonomous, to manage on one’s own. It’s really often used when talking about children leaving their parents’ house for example.

- À 35 ans, ses parents ont décidé qu’il était temps qu’il vole de ses propres ailes : ils ne veulent pas continuer à le loger et le nourrir ! (At 35, his parents decided it was high time he managed on his own: they don’t want to keep on accommodating and feeding him!)

- Après des années de salariat, elle décida de voler de ses propres ailes et de créer son entreprise. (After years as a salary woman, she decided to strike out on her own and create her own business.)

- Maintenant que le stagiaire a appris toutes les techniques, il est temps qu’il vole de ses propres ailes : on ne peut pas continuer à l’accompagner dans chaque tâche. (Now the trainee has learned all the techniques, it’s time he manages on his own: we can’t keep on supporting him in every task.)

There’s another bird related expression with a similar sense: “quitter le nid” (literally, “the leave the nest”), which specifically means leaving one’s parents’ house.

Reste pas planté / plantée là !

Here’s yet another expression where we often skip the full negation in French. The correct sentence would be “Ne reste pas planté / plantée là !” (literally, “Don’t stay planted there”).

It quite negative and is meant to point out to someone that they are being inactive, not doing anything, although there’s something important and urgent to handle.

- Ne reste pas planté là, la maison est en feu il faut éteindre l’incendie ! (Don’t just stand there, the house is on fire, we have to put out the fire!)

- Ne reste pas plantée là, tu vois bien que je suis blessée ! (Don’t just stand there, can’t you see I’m injured!?)

- Le bus va arriver, ne reste pas planté là, il faut finir nos valises. (The bus is coming, don’t just stand there, we have to finish packing.)

- Ne reste pas planté devant la télé, viens m’aider à faire la cuisine. (Don’t just sit in front of TV, come help me with the food.)

This expression is pretty easy to visualize and remember: it describes someone who’s standing (or sitting) still without moving, just as a plant doesn’t move from where it was planted.

Ne pas y aller par quatre chemins

This expression is only used in the negative form and is very similar to “mettre les pieds dans le plat”.

However, there is a subtle different: “mettre les pieds dans le plat” is about being very direct regarding one particular topic. “Ne pas y aller par quatre chemins” (literally, “not going there by four ways”) means being very direct in general.

- Elle n’y va pas par quatre chemins, parfois elle blesse ses collègues à force d’être aussi franche, mais au moins on sait ce qu’elle pense. (She doesn’t beat around the bush, and sometimes she hurts her colleagues by being so crude, but at least we know exactly what she’s thinking.)

- Dis-moi la vérité, n’y va pas par quatre chemins, je n’ai pas beaucoup de temps. (Tell me the truth, don’t beat around the bush, I don’t have much time.)

Soûler

The verb “soûler” (to get someone drunk, to intoxicate) can also be written “saouler” ou “souler” (the latter is a revised spelling that didn’t exist initially). Whichever spelling you choose, the pronunciation is the same.

When used literally, it means having someone else drink so much that they get tipsy. It’s pretty rare to use it literally, there are few situations where you would make someone drunk on purpose (unless you have bad motives).

- Il a soulé sa sœur au whisky pour la faire dormir. (He got his sister drunk with whisky so she would sleep.)

When used literally, we much more often use either the adjective “soul / saoul” (drunk, tipsy), or the reflective verb “se souler / se saouler” (to get drunk).

- Je suis complètement soule, je n’aurais pas dû boire autant ! (I’m totally drunk, I shouldn’t have drunk so much.)

- Il s’est soulé toute la nuit, on n’avait aucune idée d’où il était, on était morts d’inquiétude ! Pendant ce temps, lui, il s’amusait au bar ! (He was out drinking all night, we had no idea where he was, we were worried sick! Meanwhile, he was having fun at the bar.)

Figuratively, however, we can use this verb to say that someone or something got on our nerves. There’s another verb with the same meaning: “gaver” (force-feed, stuff). We often use that verb to say we ate more than necessary, even more than the body can bear sometimes. In each case, it literally means forcing something down the throat of someone, and figuratively it means forcing something into their hears or head, or forcing them into a certain situation or state.

- Arrête d’écouter ta musique à fond, tu me soules ! (Stop playing your music so loud, you’re annoying me / you’re boring me / you’re driving me nuts / I’m sick of it!)

- Il me soule à me parler de la Révolution française, je ne m’intéresse pas à l’histoire. (I’m sick of him talking about the French Revolution, I don’t give a damn about history.)

- Ça me soule de devoir travailler cinq jours par semaine, j’ai envie d’être en weekend tout le temps moi ! (I’m so sick of having to work five days a week, I want it to be a weekend all the time!)

- Le prof m’a trop soulée avec ses remarques à propos de mon manque d’attention. (The teacher really annoyed me with his remarks about me being absentminded.)

- Ma sœur me soule à ne jamais mettre la vaisselle dans le lave-vaisselle. (My sister gets on my nerves because she never puts her dirty dishes into the dish washer.)

Find more French expressions about being drunk on Substack

Jeter un blanc froid

In the video, I used the expression “Jeter un blanc”, but it seems it not an official expression. The correct one is “Jeter un froid” (literally, “to throw a cold”, in the sense “coldness”, not the sickness). There’s an equivalent in English: “to cast a chill”.

One could say that if you “mets les pieds dans le plat”, it could “jeter un froid” in the conversation. (Maybe this one is really worth reading in French: “On pourrait dire que quand quelqu’un a mis les pieds dans le plat, ça risque de jeter un froid dans la conversation.”).

It means creating an embarrassing silence, or making the conversation difficult because of embarrassement.

- Quand elle a commencé à raconter sa vie sexuelle pendant le repas de famille, ça a jeté un froid dans la discussion. (When she started telling about her sexual life during the family reunion, it put a damper on the conversation.)

- L’employée a commencé à faire des reproches à ses collègues pendant une réunion avec les clients, ça a jeté un froid sur les négociations. (The employee started criticizing her colleagues during a meeting with the clients, which put a damper on the negotiations.)

- Cet échec commercial a jeté un froid dans l’équipe. (This commercial failure cast a chill over the team.)

Pousser à (+ verb)

Here, both literal and figurative meanings are really similar. “Pousser à” (literally, “pushing to”) is used to express that we’re pushing someone to do something. In some cases, it could literally mean pushing someone in the back to force them to do something, but figuratively, we can push someone without physically touching them.

It can be positive or negative, it can mean “trying to force someone” or “encouraging someone”, or something in between. Therefore, English translations can vary based on the context and the exact idea we want to convey.

- Il m’a poussé à accepter ce job alors que j’hésitais. (He encouraged me to accept the job / He pushed me to accept the job / He urged me to accept the job although I hesitated.)

- Je voulais faire des études d’informatique mais elle m’a poussé à choisir la comptabilité. (I wanted to study Computer Science but she urged me to choose accountability.)

- Elle m’a poussée à étudier plus, grâce à elle j’ai fini mes études avec une mention “très bien”. (She encouraged me to study more, thanks to her I completed my education with “high honors”.)

Pousser à bout

There are many expressions using the verb “pousser” (to push). This one is really negative. It means pushing someone to their limits (literally, “pushing to the end / the tip”).

- Mon chef m’a poussée à bout pour m’inciter à démissionner. (My boss pushed me to the limit to make me quit.)

- Aujourd’hui les clients m’ont vraiment poussé à bout, ils étaient tous impolis et n’ont pas arrêté de me solliciter. (Today, customers really pushed me to my limits. They were all rude and kept asking me for things.)

Avoir beau

This expression (literally, “to have beautiful”) means we invest a lot of energy and efforts in something, but the results are disappointing.

- J’ai beau faire des heures supplémentaires au travail, on ne me donne pas de promotion. (No matter how much overtime I do at work, I don’t get promoted.)

- J’ai beau lui écrire des petits mots doux tous les jours, il doute encore que je l’aime. (Even though I write him sweet little notes every day, he still doubts that I love him.)

- J’ai eu beau m’excuser encore et encore, elle ne m’a jamais pardonnée. (No matter how many times I apologized, she never forgave me.)

I hope you enjoyed the quiz, if so, please like the video on Youtube!

Which of those expressions is the most difficult to understand for you?